The Wrecks of Ogasawara

By Charles T. Whipple

The hulk of the Hinko Maru lies within snorkeling distance from shore.

The sun kisses the horizon, a deep orange ball that floats slowly out of sight. No coral colors adorn the skies because out here 520 miles from the Japanese mainland, there is no pollution, no airborne dust, no microscopic particles reflect the sun's parting rays. In the east, puffball clouds take on a pinkish glow. In the dusk, the bright blue of the sea, the shadowy mountains, and the black silhouettes of nearby palms could well be a scene painted on a music box. Lift the lid, and you'd hear the music of wavelets lapping at the beach.

Brilliant tropical fish offset the dull colors of rusted plating.

You're on subtropical Chichijima, the main island of the Ogasawaras. The address of the dive shop reads Tokyo; yet you could hardly be farther from the chaos and confusion that typifies Japan's capital city.

My summer was filled with overtime and weekend work that kept me out of the water. As one particularly big project wound down, my boss said, "Take a couple of weeks off. Go diving or something." A month later I was on the Ogasawara Maru, the sole passenger vessel plying between the Takeshiba Pier in Tokyo Harbor to Futami harbor on Chichijima.

Three hours after leaving the pier the helmsman adjusts the ship's course and she drives almost due south down the Ogasawara trough toward Chichijima with nearly 10,000 feet of water beneath her keel. Thirty hours later, she quietly slips alongside the quay at Futami Harbor where the islanders have gathered to meet the ship. I hoist my camera bag and diving gear on my back and stagger down the gangplank. A tall man in aviator sunglasses awaits me. For the next 10 days I am at his mercy -- Yamada-san runs KAIZIN, one of Chichijima's four diving operations.

The Ogasawaras (also known as the Bonin Islands) consist of four island groups: the Keitas, the Chichijimas, the Hahajimas, and the Volcanoes -- best known for Iwojima, where fierce fighting occurred during WWII. Chichijima is the largest of the Ogawawaras, just over eight square miles with some 1,800 inhabitants, not counting visitors. Nevertheless, its town of Omura is definitely part of Tokyo, complete with meticulously paved streets, broad sidewalks, and traffic lights.

Yamada-san loads my paraphernalia into his van and drives me around the mountain to Townhouse Mitsu. Friends in Tokyo recommended the inn as the very best on Chichijima -- the rooms have TVs, air-conditioning, and western-style beds. And Mitsu's food almost defies description. "Someone will pick you up at 8:30 tomorrow morning," says Yamada-san. "We'll go diving." And diving in the Ogasawaras is spectacular, especially the wrecks.

The underwater plateau beneath the Chichijima islands is 300 to 500 feet deep. The islands are peaks of basalt, sand, and cinders that have shoved their heads above the water. A hundred yards from the cliff line may put you in 150 feet of water. So most of the wreck dives are 95-120 feet down.

The first day's diving was at Takinoura, a large bay and roadstead on Anijima, the island just north of Chichijima. The Yayoi Maru lies bow to the beach, sunk by American dive bombers. After 50 years, its plating is no longer visible under its covering of corals.

Yuzen angelfish are indigenous to warmer Japanese waters.

We enter with a giant stride off the stern of Island Queen, KAIZIN's 55-foot Yanmar dive boat. The captain's thrown a buoy to mark the wreck. Because of the current, we each submerge the moment we've entered, then group around the buoy anchor. I enter next to last. I hook my camera lanyard to my BC, and start checking settings as I drift toward the bottom. The ship sits akimbo, its radio tower broken off and lying in the sand on the far side. Schools of amalco jacks and striped jacks streak by. As I near the bottom, a skate shakes off its sand camouflage and moves a bit farther away before settling down and shuffling another load of sand over itself.

I check my buddy, and we decide to move toward the bow. Gaggles of striped fusiliers dart through the ironwork. You see keyhole angels, butterfly fish, and the lovely yuzen angel that's indigenous to the warmer Japanese waters. Spotted sweetlips hover just above the ship's plating. Marten's butterflies flit among the coral. Light from the weak sun comes through 80 feet of clear blue water to give the scene an otherworldliness that tells me I am an alien in this realm -- here only for fleeting moments to marvel and to observe before reaching the limits of my life support. It's awesome.

After a decompression stop at five meters, the guide fills his marker with air and lets the two-meter orange rod pop above the surface to tell everyone (including unobservant fishing boats) that divers are surfacing. We surface and bob about as the Island Queen backs up to us. Exit is a cinch with the boat's got huge stainless steel boarding ladder stretching across the entire stern.

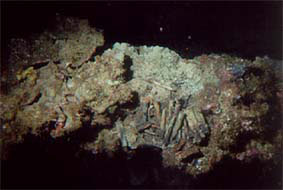

A pile of machine-gun bullets molder in the hold of the Fuju Maru.

Day two brings only one, deep dive. The Fuju Maru sits upright on the sand, 145 feet down. Her deck forecastle is at 90 feet and the cargo deck at about 100. Back of the second cargo hatch, nothing's left but mangled steel and some Dai Nippon Beer bottles. KAIZIN dive master Miki Sakurai is my buddy for this incredible dive.

We hang above a cable reel atop the forecastle as a school of striped jacks swirls around us. Ladders lead down to the cargo deck where we see the huge hatches gaping open. The entire surface is clothed in brain coral, ryumon coral, the dangerous ao coral, and other species that I don't recognize. Yuzen butterflies and angels peck at polyps. Miki points over the side. A truck lies upside down, undoubtedly thrown from the deck by the explosion that sank the ship. We drop into the cargo hold. Thousands of rounds of ammunition for rifles and machine guns litter the floor, looking as deadly today as they were half a century ago. Miki shows me tins of rations, unexploded 250 kilo bombs, and drums full of gunpowder. The old freighter smells of war. It's a grim reminder of darker days.

Too soon my computer tells me it's time to ascend. We float gently toward the surface, and the grizzled shape of the old cargo vessel slips slowly out of sight.

The Island Queen's 550 horsepower diesel puts us up on a plane and we head for Futami Harbor at 25 knots. I spend the rest of the day exploring some of the caves that honeycomb the island. I walk to Sakaiura Inlet where the Hinko Maru lies stranded on the reef. The owner of Townhouse Mitsu told me she was torpedoed at the mouth of the bay and her captain rammed her on the reef so his crew could escape. Now she's a good snorkeling spot, lying only 50 yards off the beach.

The Daimi Maru lies on her side in the silt-like coral sand, facing Futami

Harbor.

In early 1945, the Daimi Maru swung at anchor deep in Futami Bay near Kaname Rock. She was sunk by Allied aircraft and settled on her side in the fine coral sand 33 meters down. We dove on the ship after two days of brisk westerly winds that drove waves into the bay, stirring up the fine silt-like sand on the bottom. Visibility was down to about 15 meters. Our dive had a specific purpose. Two large gray nurse sharks (called Sand Tigers by the locals) had taken up residence in the Daimi Maru's cargo hold, and we were going for a visit.

We float down the weighted buoy line toward the dark shape below. Daimi's encrusted side came into view, the buoy anchor weight resting in the sand next to it. Slowly we move to the far side and dropped over the edge. The cargo holds gape like huge maws, their interiors black, their contents invisible. Eyes searching the shadows, we hug the superstructure and move closer. No sharks.

Carefully, we approach the cargo holds from the bow through the murky water. Yamada-san starts into the forward hold, then suddenly backs out. He points upward. There they are. Two big nurses. They look three meters long to me, but are probably closer to two and a half. It's my first close encounter and wouldn't you know, my new camera is on the wrong setting, and I can't click a shot.

In the afternoon, Miki and I dive on the Daimi Maru again, this time with the camera in proper working order. Still, the water is so murky the shots don't come out as I'd hoped. A third dive on the ship next morning finds the sharks gone. "The sharks are taking the day off, too," writes Kasai, the guide, on his magnetic board. It is, after all, a national holiday in Japan.

For all its ferocious visage, the sand tiger shark is quite docile.

KAIZIN always puts the lunch hook down in a good snorkeling spot. One is over the scattered bones of a freighter near Anijima. Another is Shark Inlet on Minamijima, where certain seasons bring you close encounters with white tip and sand sharks. The Keita Islands are a favorite, too. Most people go there for the dolphins (not in winter), but the cove is teaming with fish because everyone throws the remanent of their lunches to the fish. Let a boat enter the cove and the fish swarm in anticipation.

December through March, humpback whales migrate past the Ogasawaras. Often you can get diving boats to take you out for in-water photo sessions. While I was there, however, the humpbacks had yet to show up. Nor was it the season for dolphins. So I was not able to swim with them either. Another time.

And there will be another time.

TRAVEL INFO.

The Ogasawaras are in the Pacific, stretching from longitude 27 degrees 30' N to 24 degrees 10 ' N and from latitude 140 degrees 50' E to 142 degrees 10' E. Chichijima is 520 miles due south of Tokyo.

![]() HOW

TO GET THERE

HOW

TO GET THERE

The Ogasawara Maru of the Ogasawaru Steamship Line makes one round trip per

week, staying in the islands for two, three, or four nights per trip. To fully

enjoy the trip, we suggest skipping one return sailing for 11-12 days round

trip.

![]() CURRENCY

CURRENCY

Japanese yen. Dive shops accept credit cards (MasterCard and Visa) but most

inns and shops do not. Take plenty of cash.

![]() ACCOMMODATION

ACCOMMODATION

Townhouse Mitsu's owner speaks English. Almost no one else on the island does,

although diving is no problem. There are about 40 inns and four hotels on

Chichijima. Prices range from 3,500 yen a night for bed only to 30,000 yen a

night for bed and two meals at a hotel. All of the inns and hotels have a

place to hang wetsuits, and you don't have to worry about theft. (US$1.00 =

120 yen)

![]() FOOD

FOOD

If you choose, you can fend for yourself, as some inns have small kitchens.

Most inns and the hotels offer breakfast and dinner in the price. The food is

Japanese, mostly seafood, and very fresh.

![]() HEALTH

HEALTH

There is a clinic on Chichijima, but the Japanese Self Defense Forces come by

helicopter to pick up serious injuries or illnesses and fly them to Tokyo.

There are no snakes and the mosquitoes are not disease-bearing. Lots of

snails.

![]() CLIMATE

AND DATES FOR DIVING

CLIMATE

AND DATES FOR DIVING

Dive year round. Air temperatures are 64-65 degrees F in January and February,

but water temperatures are about 77-78 degrees. The island is hit by some

typhoons, but it usually means only two days are lost. With the many spots

around Chichijima, there's always a sheltered place to dive.

![]() VISIBILITY

AND CONDITIONS

VISIBILITY

AND CONDITIONS

Winter brings big Pacific swells so you can't count on getting to the Keitas

where the dolphins are. Still, Minamijima, just south of Chichijima, is often

visited by bottlenose dolphins, too. Spring and summer months are best for

swimming with dolphins. Whales are in the roadsteads December through March.

Chances of getting close are excellent. The creatures have now lost their fear

of boats and come close alongside.

![]() OTHER

ACTIVITIES

OTHER

ACTIVITIES

Windsurfing, seakayaking, moped riding, bicycle riding, hiking, picnicing,

tennis, gateball, softball, beachcombing, war relic hunting (be careful), bar

hopping (all three or four bars) -- no movie theaters, no discos.

![]() BOOKINGS

AND PRICES

BOOKINGS

AND PRICES

There are no package tours to Ogasawara. At year-end, late April-early May,

and July and August, accommodations are usually booked far in advance. Ship

fare is 22,140 yen each way for adults (half for children 12 and under and

infants free, one per adult fare). Student fares are 17,720 yen each way.

Fares are slightly higher in July and August, which are summer vacation months

in Japan. JTB or Kinki Nippon Tourist would be the best place to do your

bookings.

Charles Whipple is a writer who has lived in Japan for more than 20 years. He is an avid diver and often contributes diving articles to Australian, New Zealander, Japanese, and American diving magazines. He's fluent in Japanese and willing to help any diver get acquainted in Japan.

***12/24/2023 update: Mr. Charles T. Whipple passed away in 2019. Rest in peace.

Copyright of the article and photos on this page were reserved for Charles Whipple. The copyright now belongs to the person who has inherited it.

Posted June 3, 1998

If you have ever dived in Ogasawara, I am almost sure that you will be

yearning (right word?) to be back there... as I am, reading Mr.

Whipple's this Ogasawara report. I thank Mr. Whipple again

for sending this article for my site.

For Ogasawara related links, check Information on

Ogasawara diving and islands as well - Junko Pascoe